Writing about History without "Infodumping"

January 1, 2025

A lot of my games are historical fiction or otherwise historically-inspired. Oftentimes, this history is intricately woven into the gameplay. So, how do I impart the most important information to players? Ideally, they should absorb the information effortlessly, without even consciously thinking about the fact that they're learning history while playing the game. Today, I'd like to use Beyond the Silk Sea as an example and go over the lessons I've learned from working on it.

Inspiration

I'm a big fan of Magic: the Gathering, and I listen to Mark Rosewater's Drive to Work podcast all the time. He has a series of episodes called "Lessons Learned" wherein he revisits an old Magic set and reflects on the game design takeaways he gained from working on it. It's particularly insightful because the distance allows the designer's thoughts to mature and change. In Mark Rosewater's case, the added context of how the set was received by players upon release provides even more food for thought. It's like a post-mortem deluxe edition.

That's what I'd like to do with Beyond the Silk Sea today.

Background

Beyond the Silk Sea is a visual novel RPG set in Tang Dynasty China. You play as Severius, a lost soldier from the Byzantine Empire. One day, she winds up in the gardens of the emperor's palace. Trespassing is punishable by execution, but the princess Meixue manages to talk the emperor into sparing your life. The deal is that Meixue is given thirty weeks to train you into a model citizen, after which you'll be executed if the emperor still doesn't like you.

Mechanically, the game is very similar to "character raising" games like Long Live the Queen.

History Blurbs

Sometimes, a character will mention something for which the player might want additional historical context. When this happens, a little notification appears in the corner:

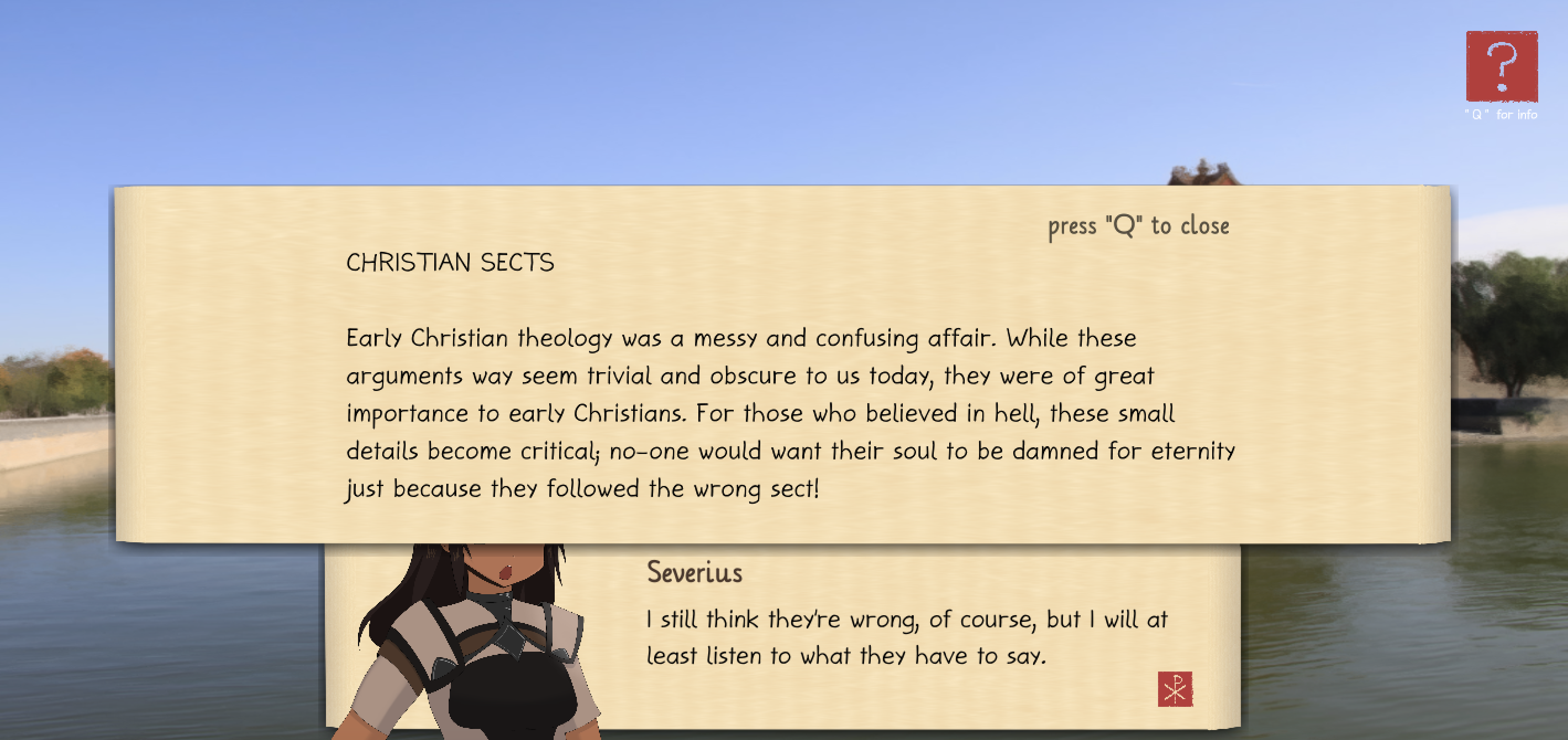

This signals that the player can view a pop-up window with a short snippet of historical information:

This information is, by design, non-technical and easy to read. I styled these "blurbs" after Civilopedia entries, the "ID questions" they make you do on history tests, and other tooltips I've seen in games. The UI notification should be larger and easier to see, but that's beyond the scope of this blog post.

Writing so People Will Care

It's so important to write succintly and with enthusiasm so that people will read. In a recent interview, the senior historian at Firaxis mentioned that undergraduates just don't read and that he hopes Sid Meier's Civilization 7 (and by extension, games) can help encourage people to be curious and do more research on their own.

Who's to blame? TikTok? Society? Who knows. But what we can control is our own writing. And so, you've got to make sure your enthusiasm shines through in your writing. You've got to make it immediately clear why "this particular subject in history" is so interesting, so cool, so worth-looking-up-on-Wikipedia-later-over-dinner.

Okay, that's nice, but how?

You can see this at work in this blurb about Chang'an. By centering facts about its size and diversity, I'm trying to get readers to feel impressed and think: "Wow, this place sounds important," so that their attention is captured for future lessons about Chang'an later on in the game. It's all objective, factual information, but the order in which you present facts—and which facts you choose to include and exclude—really matters. If there's one takeway you get from this post, it should be that it's very much possible to write about history in an engaging way without sacrificing historical accuracy.

Writing with Passion

Of course, it's a little easier to get people excited if you allow yourself a little flexibility from the regular formal, historical writing style. After all, everyone always says it's way more interesting to hear a professor lecture on something they're really passionate about! Since my goal was to get players excited enough about history to want to go out and do their own research later on, I wrote about historical events in a casual, ethusiastic tone:

Note that we are still remaining factual; I've just editorialized a bit. Of course, you have to be careful when doing this:

This is a blurb I would re-phrase. My intention here was to explain why specific, one-word differences in scripture could sometimes be so important to medieval Christians. I would take out the "messy and confusing" and "while these arguments way [sic] seem trivial and obscure to us today" parts, since I don't want to prompt the reader to think of theology that way. If they came in thinking that, the blurb will provide a new perspective. If not, there's no use in bringing up that dismissive viewpoint.

For Want of a Letter: A Short Tangent on Early Christian Theology

Even though I'm not particularly religious myself, I have always found the stories of early Christian theology to be really fascinating. But whenever we visited the subject in-class, my classmates found it really, really boring. They'd say: "Who cares about this stuff? Why is a one-word difference in scripture so important to these people? Don't they have better things to be worrying about than the difference between 'homoousios' and 'homoiousios?'"

My professor explained it like this: Imagine you are a poor, 4th-century peasant. Your life is filled with hard labor, and you cherish what small pleasures in life you have to look forward to. To you, the idea that all of your hard work will be repaid by an eternity in heaven sounds like a pretty appealing deal.

As someone who earnestly believes in salvation, now imagine how distressing would it be to suddenly face the news that you might be going to hell and experiencing an eternity of pain and torment—all because you believed in the wrong thing!

With this context, the early Christian schisms and ecumenical councils aren't just a matter of "life-or-death," but a matter of "eternal life" versus "eternal torture." Really makes these early Christians seem more relatable, right? At the very least, you can empathize with their position. Empathy, relatability, and understanding are all important in getting players excited about history and wanting to learn and read more, but that's beyond the scope of this blog post.

When the Player Simply Will Not Read

In terms of game mechanics, the "history blurb" mechanic is great because it puts the player in control of how much extra content they're reading. At the Game Center, I remember one of my favorite professors say that: "Sometimes, it's not possible to get all of the necessary information to every player, because some players just don't read. In these cases, the goal of a designer is no longer 'give the player all of the information.' The goal is now to make them feel like it's their fault that they're confused, not the game developer's." And if it's highly technical information that can only be gained by reading, not through gameplay, then: yeah, it kinda is their fault.

With the history blurbs, the player can decide if they're feeling like reading more information or not. If they're confused, the history blurb will give them much-needed context. If not, I'm not cluttering up the dialogure with unecessary exposition. If they choose to ignore the history blurbs, and are later confused, that's not ideal—but at least it won't result in a negative Steam review about how the game doesn't explain anything. The player will know that they had the opportunity to clear things up and that they chose not to do so.

The Dialogue

The main focus of this post has been the history blurbs. But in order to get players caring about history, all of the game's writing must support that goal. Players get sucked into intricate fantasy worlds all the time, so why how can we make them feel the same way about the "worldbuilding" of the real world?

I'll discuss a few examples from Beyond the Silk Sea to illustrate three techniques I used to try and get players as invested in Tang Era China as they might get in The Elder Scrolls:

- Casual Language

- The Right Timing

- Having a Good Story

Remember: the goal is to make players curious and make players care, so that the game is a "gateway drug" to future reading/research. All of these techniques directly further that goal.

Casual Language

In all of my games, my characters speak in common, present-day English. This is because, especially in games based on history, I want them to feel relatable. People are quick to "other" people who lived in the past. I want players to think "Hey, that character sounds like my friend when they're angry about traffic" or "Wow, Meixue feels the same way about her brother as I do!" Seeing oneself or one's friends/family in a character is a very fast way to get a player to like a character, and I find that this is easier to do when the character sounds like someone you might meet in the present-day.

I would like to note that this does NOT mean that Severius and Meixue are running around dabbing and saying "skibidi ohio rizz." I mean that I'm not making them speak in very formal language, which would have been expected of them, given their historical context.

The Right Timing

Think of your favorite fantasy world. How did you come to learn all that lore? You certainly didn't sit down and read it all in one sitting (and if you did, you're a total nerd and I respect that). You likely got hooked on the characters and the gameplay first, then learned the lore as it became relevant to the story.

By far the most important pieces of historical context are those that explain Byzantium/Rome/Fulin and the Tang Era court. I could have begun the game with a quick prologue/narrative intro, as some fantasy games do. Instead, I asked myself: "When exactly does the player actually need to know this?" and I placed the exposition accordingly in the game's script.

The game begins with Meixue finding the player character unconscious in the palace gardens, and the prologue establishes the high stakes (execution) and some empathy for Meixue's character (she's willing to do a lot to help a total stranger). As a historian, I love history. But I also know when I need to let the history lessons "take a back seat" to get the player adequately "invested" in the narrative first. That way, when they finally do learn about Emperor Tang Taizong, it's in the exciting context of "This is your new girlfriend's dad!" instead of being a seemingly-unrelated snoozefest.

Having a Good Story

Also known as "Making Things Up." It's historical fiction, after all. Even the best biographers do a bit of editorializing in order to create books that are interesting to read. I want to be clear—I am not talking about introducing inaccuracies. But even in very formal, stuffy academic history writing, at some point, the historian has to make their best guess at the way things might have been based on the available evidence. It's important to interpret with intention—if you're going to simplify something or extrapolate into a vision of a character or event, doing so should A. be supported by the primary sources, and B. actively further your narrative goals

The court of Tang Taizong was a colorful place filled with great characters, and there's a lot of good material for scenes that I pulled directly from the primary sources. One such example is the match between two imperial cuju (medieval Chinese football) teams—such teams actually existed, and there were women's leagues.

When it came to writing the two princes, I had to get a little creative. The sources say that Li Chengqian loved Turkic customs so much that he made a Turkic-inspired camp in the middle of the throne room and had a tent in there and roasted goats in there and everything. I thought it would be fun, then, to give this prince a laid-back personality—someone who isn't too concerned with traditions and formalities. It only made sense, then, that his brother Li Tai would be the opposite—bookish and fastidious. The prince's personalities weren't explicity stated in the sources, and I felt that this was an interesting dynamic to explore in the writing. It's not like any of this is wild conjecture, either—they're plausible guesses at the personalities of historical figures that are based in actual details about how they lived their lives. You've got to strike a delicate balance between fact and fiction.

Endings are Hard to Title

If you read this far, thanks for reading! I hope this was helpful and interesting. You're definitely not in the subset of students that Dr. Johnson is worried about. I'll be doing more of these in the future, and announcing them on my Bluesky!